I regularly encourage my biblical studies students that one aspect of training ourselves to interpret the Bible well is to read good literature. Good literature helps to round us out as human beings, and it simply trains us to read well. C. S. Lewis illustrates this well in his classic essay, “Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism.”

This point is powerfully made by Anthony Esolen in his article, “Pauline Scholar, Meet Homeric Scholar: How Textual Analysis Misses Authorial Genius & Literary Inspiration,” in the July/August 2013 issue of Touchstone Magazine. Esolen is a professor of English and widely published author- someone who is on my “read whatever he writes list.” In this brief article Esolen draws from his years of working with classic literature to question some of the literary criticism often used on New Testament studies. He notes that though for a long time scholars insisted that Homer’s poems, Beowulf, and other works were not actually the work of one man, the tide has turned and the skepticism has been shown to be unfounded. He describes the skeptical scholarship as working with “all the wrong assumptions,” typically requiring authors to write the way we would or in the ways we expect.

Here is a key paragraph:

“Linguistic analysis alone is pretty good at telling us, within a century, when something was written, and at confirming that the man who wrote Richard III also wrote Macbeth. It’s not very good for establishing chronological order within a century, not for confirming that the man who wrote one thing did not also write another. On linguistic analysis, apart from authorial affirmation, we can determine that the author of the Gospel of Luke is also the author of Acts. But beyond such conclusion we dare not go with confidence. We cannot say that one author could not have written Romans and Ephesians, which are a foot or two apart, as compared with the furlong that separates the author of the first part of The Dream of the Rood from the same man when he’s writing the second part, the mile that separates Milton’s satirical sonnets from the sweet Il Penseroso, and the light year that separates The Merry Wives of Windsor from King Lear.”

This literary perspective is important for various discussions in New Testament studies including the authorship of the Pastorals. Given the wide range of style and vocabulary used by other prominent writers in history we should be cautious about what can be determined concerning authorship by variations in vocabulary and style. Can we really say with such self-assurance, as I have heard scholars do, what Paul could not have written?

The full piece by Esolen is well worth reading. It is not available online, but Jim Kushiner, Executive Editor of Touchstone, has graciously offered to send a complimentary hard copy of the issue containing this article to any of our readers who ask. If you’d like a copy, email jdockery@fsj.org noting that you are responding to this column and ask for a copy of the July/August 2013 issue.

UPDATE: The article is now available online and I have linked it above. Thanks to Jim Kushiner for his gracious offer during the time the article was not online.

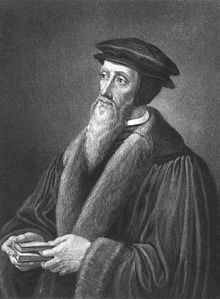

I am working through Calvin’s sermons on the Pastoral Epistles in preparation for the Reformation Commentary on Scripture volume on the PE and editing a new edition of the English translation of these sermons. Today I came across this strong statement in Calvin’s first sermon on 2 Timothy.

I am working through Calvin’s sermons on the Pastoral Epistles in preparation for the Reformation Commentary on Scripture volume on the PE and editing a new edition of the English translation of these sermons. Today I came across this strong statement in Calvin’s first sermon on 2 Timothy.